I have an alter ego or, as it is now known on the internet, an avatar. My avatar looks like me and sounds at least a bit like me. He pops up constantly on Facebook and Instagram. Colleagues who understand social media far better than I do have tried to kill this avatar. But so far at least they have failed.

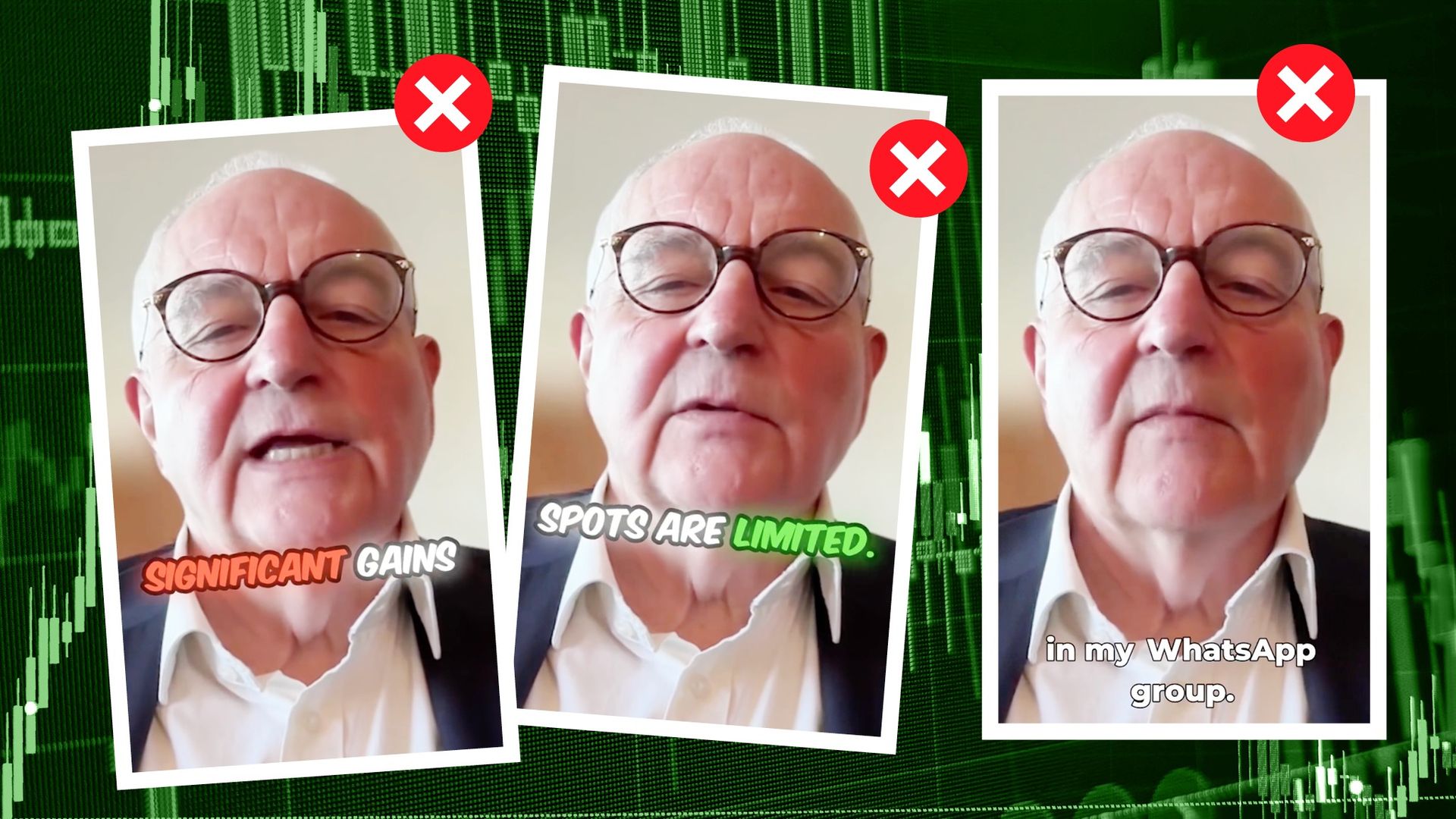

Why are we so determined to terminate this plausible-seeming version of myself? Because he is a fraud — a “deepfake”. Worse, he is also literally a fraud: he tries to get people to join an investment group that I am allegedly leading. Somebody has designed him to cheat people, by exploiting new technology, my name and reputation and that of the FT. He must die. But can we get him killed?

I was first introduced to my avatar on March 11 2025. A former colleague brought his existence to my attention and I brought him at once to that of experts at the FT.

It turned out that he was in an advertisement on Instagram for a WhatsApp group supposedly run by me. That means Meta, which owns both platforms, was indirectly making money from the fraud. This was a shock. Someone was running a financial fraud in my name. It was as bad that Meta was profiting from it.

My expert colleague contacted Meta and after a little “to-ing and fro-ing”, managed to get the offending adverts taken down. Alas, that was far from the end of the affair. In subsequent weeks a number of other people, some whom I knew personally and others who knew who I am, brought further posts to my attention. On each occasion, after being notified, Meta told us that it had been taken down. Furthermore, I have also recently been enrolled in a new Meta system that uses facial recognition technology to identify and remove such scams.

In all, we felt that we were getting on top of this evil. Yes, it had been a bit like “whack-a-mole”, but the number of molehills we were seeing seemed to be low and falling. This has since turned out to be wrong. After examining the relevant data, another expert colleague recently told me there were at least three different deepfake videos and multiple Photoshopped images running over 1,700 advertisements with slight variations across Facebook, and Instagram. The data, from Meta’s Ad Library, shows the ads reached over 970,000 users in the EU alone — where regulations require tech platforms to report such figures.

“Since the ads are all in English, this likely represents only part of their overall reach,” my colleague noted. Presumably many more UK accounts saw them as well.

These ads were purchased by ten fake accounts, with new ones appearing after some were banned. This is like fighting the Hydra!

That is not all. There is a painful difference, I find, between knowing that social media platforms are being used to defraud people and being made an unwitting part of such a scam myself. This has been quite a shock. So how, I wonder, is it possible that a company like Meta with its huge resources, including artificial intelligence tools, cannot identify and take down such frauds automatically, particularly when informed of their existence? Is it really that hard or are they not trying, as Sarah Wynn-Williams suggests in her excellent book Careless People?

We have been in touch with officials at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, who directed us towards Meta’s ad policies, which state that “ads must not promote products, services, schemes or offers using identified deceptive or misleading practices, including those meant to scam people out of money or personal information”. Similarly, the Online Safety Act requires platforms to protect users from fraud.

A spokesperson for Meta itself said: “It’s against our policies to impersonate public figures and we have removed and disabled the ads, accounts, and pages that were shared with us.”

Meta said in self-exculpation that “scammers are relentless and continuously evolve their tactics to try to evade detection, which is why we’re constantly developing new ways to make it harder for scammers to deceive others — including using facial recognition technology.” Yet I find it hard to believe that Meta, with its vast resources, could not do better. It should simply not be disseminating such frauds.

In the meantime, beware. I never offer investment advice. If you see such an advertisement, it is a scam. If you have been the victim of this scam, please share your experience with the FT at visual.investigations@ft.com. We need to get all the ads taken down and so to know whether Meta is getting on top of this problem.

Above all, this sort of fraud has to stop. If Meta cannot do it, who will?